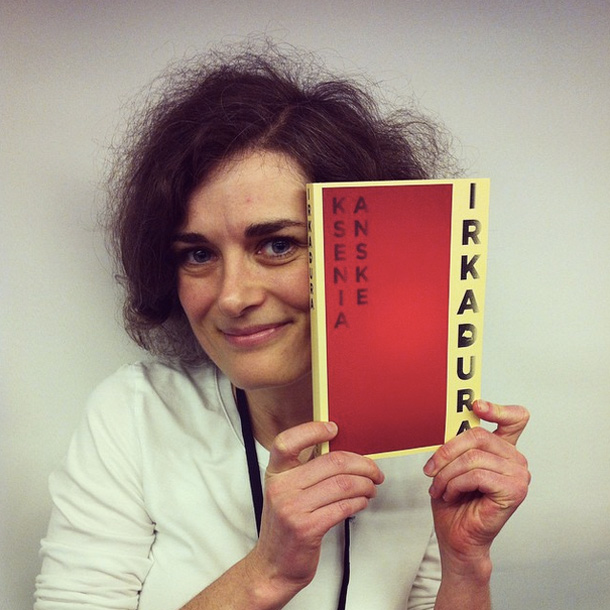

IRKADURA

A novel by Ksenia Anske, Draft 1

Chapter 1. Dura

Irka stopped talking the moment she learned how to talk. It was a sunny day. She just got done peeing into a pot and waddled over to her mother for panty pulling.

“Dua.” She said brightly. Only two, Irka couldn’t roll a proper Russian ‘r’ yet. “Dua, dua.” She heard the word dura often, not knowing that in meant female fool, under the best of circumstances. Under the worst of circumstances, it meant retarded bitch, and that’s how it was used in Marinova household, comprised entirely of women: Irka’s mother, aunt, cousin, grandmother and great grandmother, all crammed into a three bedroom flat on the last floor of a Soviet apartment building.

“Dua, dua, dua!” Irka poked the snoring shape on the mattress.

Marina Marinova grunted and opened one eye. Her normal morning started with a couple bottles of Zhigulevskoe beer. Money ran scarce this month and she couldn’t afford her hangover remedy, suffering the consequences in the form of a blinding headache. The sun didn’t help. Marina sat, reeling.

“Dua! Dua!” Irka chanted on repeat, clapping hands, her feet doing a little dance, as much as fallen panties permitted.

“Che? Wha…?” Marina blinked.

“Dua.” Said Irka uncertainly. In her short life she learned to recognize her mother’s tone of voice, predicting the future with astounding accuracy. It went down two paths, bad and not so bad.

Comprehension dawned on Marina’s face. “Che ty skazala? Whaddya say? Dura? Ya te pokazhu dura! I’ll show you dura!” Her movements, swift and precise, indicated years of practice.

Irka flew across the room, slammed into the pot and knocked it over. She bit on her tongue, hard. Warm urine seeped into her shirt. A shadow blocked the sunlight. Irka instinctively cowered. Later, she didn’t remember how she got beaten or for how long. Fortunately, toddler memory blotted out most of its contents by the time Irka turned sixteen. She did remember one thing. The garish orange curtains, they way threads hung off the frayed bottom, they way they flapped in rhythm to her mother’s fists. Since then she couldn’t stand orange things, and she stopped talking, for good. At first, due to a swollen tongue, then out of terror, then out of sheer habit.

Irka learned that being quiet had its advantages. One, women in her family stopped bothering her, thinking her an idiot and nicknaming her Irkadura. Two, men got bored of her faster. What do they always want with me? I’m so ugly, thought Irka. She hated her mousy hair, her midget height, her sizeable boobs and ass that developed way too early. School uniforms never fit her and boys constantly attempted to lift her skirt to see what panties she wore. She ignored them with stubborn silence. It was nothing compared to what she endured at home.

To remedy their financial situation, Marina occasionally brought home men, picking them up like stray dogs, the filthiest, the smelliest, and the hairiest she could find. None of them lasted long, kicked out in a few weeks by sharp glares and colorful words of Nadezhda Marinova, Irka’s great grandmother. In one case she successfully used the broom as an aid to convince a particularly stubborn specimen. With years Nadezhda’s health deteriorated and she spent her days in bed, shuffling out only to use the bathroom or drink tea. Irka’s grandmother Valentina, or Valya for short, turned a blind eye to her daughter’s antics, camping out with Sonya, Irka’s aunt, and Lenochka, Irka’s younger cousin, in the adjacent room, complete with three cats, two dogs, a rat, and a hedgehog. This left only one room for Irka to share with her mother, and, subsequently, with any man she brought home. All of them took ample advantage of this fact, using Irka as a convenient mutie pet, until they tired of both women, stole whatever was worth stealing and disappeared, leaving Marina drunk and wailing.

All, except Lyosha Ivanenko, who stuck.

He showed up at the door one day, flowers in one hand, a sack of vodka in another, a butcher who spent last three years in prison for thievery and just got discharged. He became Marina’s glorious achievement in finding the lowest scum on the streets of Moscow, the likes of which didn’t exist in the recently disbanded Soviet Union according to its newspapers and television. Irka was fifteen. Her bust burst out of the bra that didn’t fit anymore, her body showed through the hand-me-down housecoat.

Lyosha’s eyes glinted. To ascertain his fatherly position, on the very fight night he pumped Marina with alcohol until she passed out, then pressed Irka into a corner and fondled her with a sick grin. He did it in their room, but with time grew bold, handing her in the kitchen in plain view. Old Nadezhda, the only woman who would’ve given Lyosha a piece of her mind, barely showed her face. Valya turned a blind eye, coming home late and leaving early for her nursing job. Sonya and Lenochka were gone to meet young men qualified for a potential marriage.

The only positive change Lyosha brought was forcing all Marinova women to stop walking around the house in underwear or plain naked. And so, unchallenged, he stayed for a whole year, spending his days watching the small black and white TV, drinking vodka, singing post-war songs and fondling Marina in the kitchen while she cooked, winking at Irka every time she happened to look. It signified the oncoming of her nightly regimen. Marina served as an appetizer. Irka’s body was what interested Lyosha most, her ripe breasts, her fleshy thighs, and the lack of virginity between them, taken a long time ago by one of Marina’s passing boyfriends. When, Irka couldn’t remember. Resistance never crossed her mind. Trained to give up her body for the use of others, either as a punching bag or as a source of pleasure, she turned herself numb and escaped into her head.

Irka grew up with three types of touch. Hitting. Groping. And sinking of filthy limbs into her very being, making her want to puke. She always contained the urge, emptying her stomach after, while crouched over the toilet bowl on the cold floor. None of the episodes lasted long anyway, the potency of her mother’s boyfriends fluctuating roughly between a few jerks to a couple minutes at the most, that is, if they could get it up after drinking for hours. Not the case with Lyosha. He happened to maintain both a boar’s stamina and looks, or perhaps his job of slaughtering pigs rubbed off on his personality. Over the course of the year Irka’s patience ran ragged, until one night he hurt her so bad that something snapped in her. She couldn’t stand it any longer and decided to run.